Can Wearable Trackers Become as Indispensable as Smartphones?

Data privacy & analytics will determine the future of wearables

Many runners and fitness fanatics have been quick to embrace wearable wireless tracking devices for measuring physical activity and calories burned. Now, a growing number of physicians are studying whether such "wearables" can improve patients' health by spurring people to get moving.

For example, primary-care doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) hopes that wireless tracking devices can help motivate obese patients do what they haven't been able to do on their own: lose weight.

For example, primary-care doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) hopes that wireless tracking devices can help motivate obese patients do what they haven't been able to do on their own: lose weight.

Recently, MGH doctors gave FitLinxx pedometers to 126 patients with Type 2 diabetes, a disease often related to poor diet and excess weight.

The pedometers tracked how many steps the patients walked and linked to a software program that calculated whether patients met exercise goals. Based on patients' progress in meeting their goals, data from their electronic medical records, and whether it was sunny or rainy that day, patients would receive motivational tips via text message. Researchers found patients who received the tips did a better job of controlling their blood-sugar levels than those who didn't.

Another group of researchers used Fitbit gadgets to track activity levels of cardiac-surgery patients. They found that patients who moved more the day after surgery were more likely to be discharged sooner. These findings have prompted hospitals to dispatch physical therapists to study patients who weren't moving as much as doctors do not, in general, know why some patients move more than others.

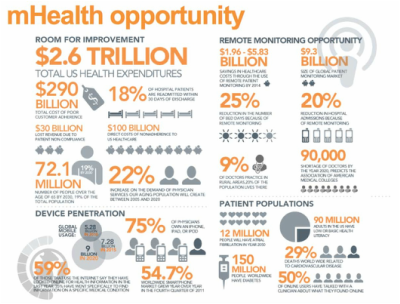

These researcher are among a growing group of health-care providers who believe that the wealth of data from these activity trackers could transform medical care. But adapting consumer gadgets for clinical use poses challenges, from doubts about the reliability of the data to technical hurdles of collecting and analyzing the information. Privacy and security concerns loom large as well. Privacy advocates worry that as Americans upload potentially intimate health information into gadgets and apps, there aren't enough protections to prevent the data from being misused.

Some physicians question whether patients will remember to wear such devices—or remember they are wearing them. That is what happened when other doctors gave wireless trackers to 30 healthy 80-year-olds. Like most of the participants in their study, they found the tracker didn't influence patients’ behavior because after a few days they forgot the device was there.

Some physicians question whether patients will remember to wear such devices—or remember they are wearing them. That is what happened when other doctors gave wireless trackers to 30 healthy 80-year-olds. Like most of the participants in their study, they found the tracker didn't influence patients’ behavior because after a few days they forgot the device was there.

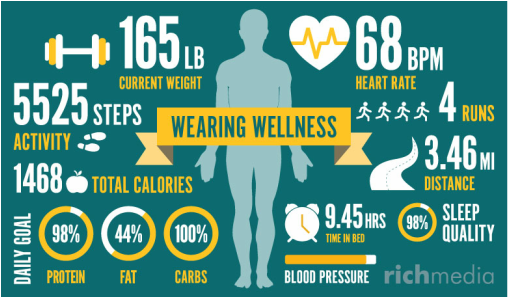

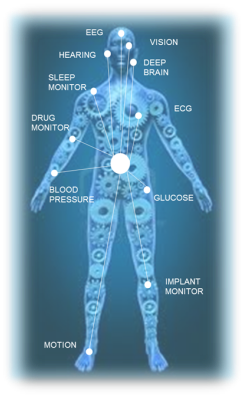

Health-tracking wearables is projected to generate $5 billion by 2016, according to Gartner Research. Such gadgets include those from Garmin, Fitbit, Jawbone, Misfit, and smaller companies like Moov. Trackers offer a range of measures—e.g., calories burnt, steps taken, heart rate, temperature, to complex data like blood pressure. More often than not, the devices are tethered to a smartphone to upload the data to the manufacturer’s computers. This continuous data stream is then used to help users to see how they are progressing over time.

With personalized data from these devices couple with and genetic data, it is creating new opportunities for healthcare ecosystem to discover what we are doing, why, influences, and ways influence whole populations in what global healthcare expertise has been driving toward for decades—that is, personalized medicine and preventive healthcare.

Trackers have been incorporated into more than 2,000 corporate-wellness programs. Cigna Corp. recently gave activity-tracking arm bands, and health coaching, to 600 employees considered at risk of diabetes at four companies. A large majority, 86%, said they were more motivated to be active as they can see their activity levels and know how much more they need to do to minimally stay healthy, based on guidelines from their physicians or other sources.

There are technical challenges for using data from consumer devices. One being that researchers often have to write interface software to extract the information from the tracker so could they can see it on other devices such tablets. Even then, the data isn’t connected to the rest of a patient's medical record. Merging data from different devices into diverse health databases, governed by varying legal protections, further complicates things. There's tremendous fragmentation of health data, and no easy way for physicians to get to it.

Some of the leaders such as Samsung Electronics Co. and Apple Inc. are trying to bridge this technical gap. Recently, they are building platforms that collect data from apps and wearables, which medical providers will be able to access. For instance, Apple is working with the Mayo Clinic and Epic, a provider of electronic medical records, to solve this problem.

Trackers have been incorporated into more than 2,000 corporate-wellness programs. Cigna Corp. recently gave activity-tracking arm bands, and health coaching, to 600 employees considered at risk of diabetes at four companies. A large majority, 86%, said they were more motivated to be active as they can see their activity levels and know how much more they need to do to minimally stay healthy, based on guidelines from their physicians or other sources.

There are technical challenges for using data from consumer devices. One being that researchers often have to write interface software to extract the information from the tracker so could they can see it on other devices such tablets. Even then, the data isn’t connected to the rest of a patient's medical record. Merging data from different devices into diverse health databases, governed by varying legal protections, further complicates things. There's tremendous fragmentation of health data, and no easy way for physicians to get to it.

Some of the leaders such as Samsung Electronics Co. and Apple Inc. are trying to bridge this technical gap. Recently, they are building platforms that collect data from apps and wearables, which medical providers will be able to access. For instance, Apple is working with the Mayo Clinic and Epic, a provider of electronic medical records, to solve this problem.

Privacy is another significant issue. Integrated managed care organizations such as Healthcare Kaiser Permanente are testing wearables in more than a dozen pilots to see if they have any medical value. However, before they start recommending the devices to their nine million members, managers want to ensure that patient information won't be misused.

A recent review of 43 health- and fitness-tracking apps by the advocacy group Privacy Rights Clearinghouse found that roughly one-third of apps tested sent data to a third party not disclosed by the developer. One-third of the apps had no privacy policy. There are organization like the Consumer Wellness and Wearables Working Group addressing the data privacy issues. The goal of the working group is to build on best practices that support consumer trust, as well as to develop responsible guidelines for appropriate research and other secondary uses of such data.

Consumer wearables fall into a regulatory gray area. Health-privacy laws that prevent the commercial use of patient data without consent don't apply to the makers of consumer devices.

Today, there are no specific rules about how vendors can use and share data. This will likely change as wearables data become more common in making diagnostics. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently said it won't regulate apps that aren't being marketed to monitor a disease or condition, or to treat or diagnose a patient.

There is a ground swell into the tracking craze but, in general, consumers do not see the broader implications of the implicit consent they are giving when creating an account and giving consent to upload their data to the manufacturers or unspecified website. Once the data is upload, it can reside on computers that can be in almost any part of the world, subject to laws they may not have contemplated.

Wearable companies must start to understand the legal framework and implications across the spectrum of applications—from everyday fitness tracking, semi-diagnostics, to full scale data usage for prescribing therapeutics. The pace of change for each of these scenarios can unfold quickly and take the market players by surprise.

Data from wearables are meant to be de-identified but the reality is that data can still be tracked by to an individual since most trackers are tethered to a smartphone, whose data is personalized to the user. The wearable will advanced to do more than what is being today. There are two areas that must advance quicker than the hardware if trackers are to become indispensable and reliable—data privacy and analytics.

Without the advancements in privacy and analytics—wearable trackers will remain an ephemeral, nice to have gadgets and not live up to their full potential.

A recent review of 43 health- and fitness-tracking apps by the advocacy group Privacy Rights Clearinghouse found that roughly one-third of apps tested sent data to a third party not disclosed by the developer. One-third of the apps had no privacy policy. There are organization like the Consumer Wellness and Wearables Working Group addressing the data privacy issues. The goal of the working group is to build on best practices that support consumer trust, as well as to develop responsible guidelines for appropriate research and other secondary uses of such data.

Consumer wearables fall into a regulatory gray area. Health-privacy laws that prevent the commercial use of patient data without consent don't apply to the makers of consumer devices.

Today, there are no specific rules about how vendors can use and share data. This will likely change as wearables data become more common in making diagnostics. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently said it won't regulate apps that aren't being marketed to monitor a disease or condition, or to treat or diagnose a patient.

There is a ground swell into the tracking craze but, in general, consumers do not see the broader implications of the implicit consent they are giving when creating an account and giving consent to upload their data to the manufacturers or unspecified website. Once the data is upload, it can reside on computers that can be in almost any part of the world, subject to laws they may not have contemplated.

Wearable companies must start to understand the legal framework and implications across the spectrum of applications—from everyday fitness tracking, semi-diagnostics, to full scale data usage for prescribing therapeutics. The pace of change for each of these scenarios can unfold quickly and take the market players by surprise.

Data from wearables are meant to be de-identified but the reality is that data can still be tracked by to an individual since most trackers are tethered to a smartphone, whose data is personalized to the user. The wearable will advanced to do more than what is being today. There are two areas that must advance quicker than the hardware if trackers are to become indispensable and reliable—data privacy and analytics.

Without the advancements in privacy and analytics—wearable trackers will remain an ephemeral, nice to have gadgets and not live up to their full potential.

Next On Wearables

We are looking at wearables and its potential uses in Population Health Management.

Please contact us.

We are looking at wearables and its potential uses in Population Health Management.

Please contact us.

Activity Trackers in Healthcare

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

Vaxa Inc. © 1998-2020 All Rights Reserved

|

CONNECT WITH US

|